The Noble Experiment

Prohibition's epic failure, the history of "firewater," and how one man singlehandedly established the American vodka industry.

Hi! Welcome to Issue #2 of Quarantine Cocktail Club, written by me, Anna Callahan. This week, we’re jumping right in with an abbreviated history of prohibition, the origin story of America’s favorite spirit – vodka – and the story of the time my dad interviewed the man who brought it to the United States. Of course, I’ve included three cocktail recipes personally tested by yours truly, and trust me, they are delicious. Let’s dive on in.

The Noble Experiment

As passionate mixologists-to-be, it’s crazy how little we talk about prohibition. We read Fitzgerald, and Hemingway, and watch movies set in the roaring 20s, but all too often we forget that the alcohol consumed at the mind-blowing parties they describe was secured through a systemically corrupt regulatory system, organized crime, gang violence, and bootlegging. It’s safe to assume that the negative consequences of prohibition left the elite inhabitants of East and West Egg relatively unscathed.

If you need a refresher, prohibition was enacted as an experimental solution for the destruction alcohol had inflicted on American family life. Wine and beer weren’t as popular at the time, so whiskey was the average man’s drink of choice, and they drank lots of it – the average person’s alcohol consumption was three times what it is today. Men would leave work and head straight to the saloon before coming home and abusing their wives and children. In many ways, the Temperance Movement was protesting domestic violence, pioneered by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton who would go on to lead the suffrage movement.

But there was also a xenophobic and elitist sentiment driving the Temperance Movement – heavy drinking culture was associated with industrialization, immigrants, and the working class, and was thus seen as detrimental to Christian values. Groups like the wealthy and well-connected Women’s Christian Temperance Union used these talking points to rally public opinion around prohibition towards the end of the 1910s. The outbreak of World War I was the nail in the coffin, as activists compellingly argued that wheat, barley, and rye should be used to feed hungry soldiers rather than intoxicating draft-dodgers and housewives in their absence. On January 16, 1919, the 18th Amendment was ratified, making it illegal to manufacture, sell, or transport alcoholic beverages.

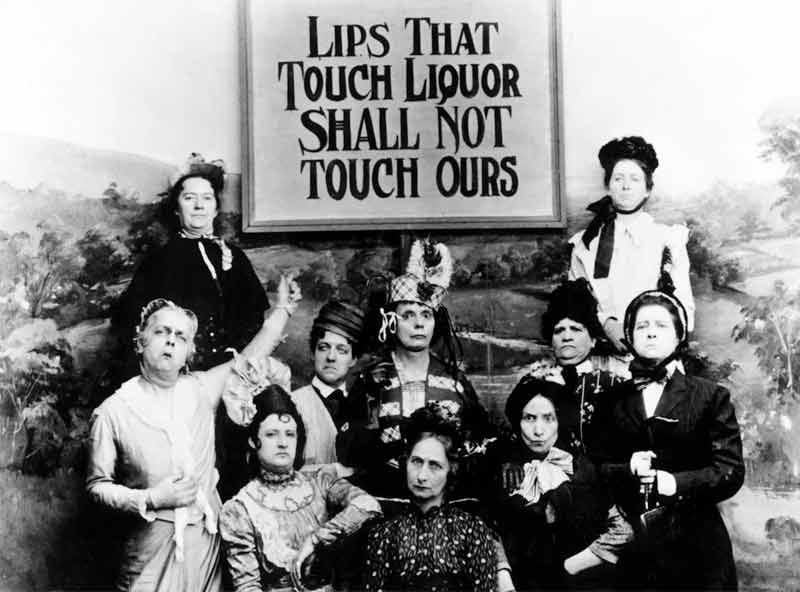

Above, a group of pro-temperance activists called “The Kansas Saloon Smashers”

Prohibition drastically changed drinking culture in the United States, as well as American life in general – but definitely not in the way legislators hoped. Americans had almost a year to prepare before the dry laws came into effect, so those who could afford to stock up continued drinking comfortably through the 20s. Most had no intention of obeying the regulations and easily found ways to circumnavigate them, like finding sympathetic doctors to diagnose them with medical disorders that could be “treated” with a “medicinal whiskey prescription.” (If anyone has a lead on one of those…please let me know). Others bribed policemen, or prohibition officers, or got directly involved in the mysterious and lucrative business of bootlegging themselves. As the illegal alcohol market became increasingly profitable, so did rates of corruption and organized crime. With private stockpiles, bootlegging, and speakeasies in cities nationwide, the 18th Amendment was only able to reduce alcohol consumption by about 30 percent.

It quickly became clear that prohibition was actually exacerbating the vices it was meant to eradicate. In Chicago, on February 14th, 1929, a cadre of Al Capone’s gang members shot and killed seven rival gangsters working for George “Bugs” Moran in a gory event that would go down in history as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Capone was making millions a year from bootlegging, and American lawmakers and their constituents had had enough. Fittingly, just as women ushered in the Temperance Movement, they were also a key factor in its repeal. Pauline Sabin, a New York City socialite and the first female board member of the Republican National Committee, successfully organized a pro-repeal movement that was largely credited for prohibition’s reversal. The 21st Amendment (which repealed the 18th) was ratified on April 23rd, 1933, marking the end of thirteen upsettingly long and dry years.

At left, the young Pauline Sabin is depicted in a painting on display at the National Portrait Gallery. At right, the July 1932 cover of Time Magazine featuring Sabin’s photograph.

Meet the Cast: Vodka

Meet the Cast is a recurring segment in which I’ll share interesting stories about the liquors we consume often, yet know so little about.

Last week we learned all about gin, the history of which turned out to be fascinating, tragic, and well-documented. This week, we’re pivoting to vodka - the spirit many college students find themselves in a love-hate relationship with. Unlike gin, the history of vodka is shrouded in mystery. While both Russia and Poland claim the title of vodka’s birthplace, most historians agree that different varieties of the spirit originated in both countries around the same time during the Middle Ages. The name vodka was derived from the Slavic word “voda,” which is interpreted as “little water.” In Poland, an early name for the beverage was “gorzałka,” meaning “to burn.” Fitting!

For centuries before vodka became many Slavic countries’ beverage of choice, it was sold and used as a powerful anesthetic and disinfectant. In 1534, the prolific Polish herbalist Stefan Falimierz wrote that different types of vodka could be used to treat jaundice, tuberculosis, headaches, memory loss, and even "to increase fertility and awaken lust." Of course, now we know that any lust felt after taking a dose of vodka was likely attributed to intoxication, not some magical property.

Soon after its invention, the production and trade of vodka became essential to both Russia and Poland’s economies. Traders soon discovered vodka’s low freezing point, meaning bottles of the spirit were much less likely to freeze and shatter in transit during cold Siberian winters. The vodka trade soon became an economic lifeline for producers and traders during this time of the year. Systemic poverty was widespread, the temperature hovered around zero degrees for days at a time, and many sought solace from their seasonal depression by reaching for the vodka bottle.

Shoppers check out vodka in a street kiosk in Moscow.

During the 19th century, regulations in Tsarist Russia limited the importation of alcohol and instead promoted the consumption of domestically produced vodka in an attempt to help stimulate the economy. As a result, it became most Russians’ drink of choice. Around this time, taxes on Russian vodka were funding up to 40% of state revenue. By 1911, vodka made up almost 90% of all alcohol consumed in the country, and it remains the beverage of choice in almost all Slavic countries to this day.

Dad Dispatch: Getting Along with Others

Dad Dispatch is a recurring segment by my father, Sean Callahan, a retired magazine editor who wrote about wines and spirits for GQ. When I ask him mixology-related questions, the answers are typically followed by long stories from “the golden age of magazines,” so I figured I’d share them.

Because of vodka’s versatility — it can be used with practically any mixer — it is the top-selling distilled spirit by volume in the US and has been for decades. The secret to its companionability is that, by law, it must be at least 80 proof (no less than 40% alcohol) after distillation with charcoal or other materials so as to be “without distinctive character, aroma, taste or color.” Thus, it gets along with everything in the mix.

Not to be confused with flavored vodkas, true vodka is a neutral spirit distilled mostly from cereal grains, like wheat and rye, or even potatoes in some Russian varieties.

In the US prior to WWII, you might find a bottle of vodka buried on the shelf of a well-stocked bar but pride of place was occupied by the brown liquors (scotch, rye, and bourbon) with their sidekicks gin and rum.

Vodka had no real presence in the consumer market until 1938 when Jack Martin, president of Heublein, Inc, a CT-based manufacturer of premixed cocktails, paid $14,000 for the rights to the name Smirnoff. The label’s former owner was a purveyor to the 19th-century Czars but had lost everything in the Russian Revolution of 1917.

There was no secret ingredient or unique recipe involved – Martin just bought the name. Since vodka was only neutral grain alcohol diluted with water, Martin knew he needed a cachet to market this novel liquor to the American consumer. He took what others saw as vodka’s blandness and turned it into a desirable attribute. No discernable taste meant no after breath, thus, Smirnoff’s slogan became “it leaves you breathless.”

Mid-century magazine advertisements for Smirnoff Vodka.

This was subtle messaging by Madison Avenue insinuating that you could have a few drinks after work and not have the tell-tale smell of alcohol on your breath. (At least until it starts to metabolize in your system and other physical conditions start to tip your handiwork.) Smirnoff’s ads, featuring celebrity endorsers and recipes popularizing the Moscow Mule, the Bloody Mary, and the Screwdriver, among others, fueled vodka sales in the 1950s and 60s to the dominant sales position it holds today.

A portrait of my father, taken by LIFE Magazine photographer and former colleague, Michael Mauney in 1992.

For a story on vodka, I called up the retired Jack Martin and he told me that for many years Smirnoff’s sales were disappointing until he noticed that one of his salesmen in South Carolina was moving a lot of product. So Jack got him on the phone. He learned that the corks in his first shipment were mislabeled “whiskey.” It turned out that the Heublein bottler had run out of plain corks during one batch of orders. The local salesman, like his customers throughout Appalachia, had never seen a whiskey that wasn’t brown and had never heard of vodka, so he’d been calling the rare new spirit “white whiskey.” It was novel, potent, and cheap. Sales took off.

“They thought it was moonshine,” Martin chuckled. “Only, legal.”

Cocktails of the Week

A vodka-themed newsletter could not be complete without a Vesper recipe. For those unfamiliar, this gin-and-vodka martini was James Bond’s drink of choice. As written in Meehan’s Bartender Manual, “the Vesper serves as a double agent in the ‘cold war’ between vodka and gin martini drinkers.” In order to pay homage to the iconic film character, the Vesper would need to be shaken, not stirred. However, stirring is the traditional incorporation method and will better accentuate the flavor of the Lillet. A warning: as the three types of alcohol might indicate, this cocktail is very potent - I recommend proceeding with caution.

Interestingly, this drink also rose to prominence as a result of the Bond movie enterprise. In the 2002 movie Die Another Day, when Pierce Brosman (playing James Bond) encountered Halle Berry (playing Jinx) on a beach in Havana, he broke the ice by offering her a sip of his Mohito.

The Bramble is one of the trademarks of the innovative British mixologist Dick Bradsell. Bradsell, famously named the “cocktail king” and credited by The San Francisco Chronicle as having "single-handedly [changed] the face of the London cocktail scene in the 1980s," invented The Bramble while working at Fred’s Club in London’s Soho neighborhood. Thirty years later, the drink is a mainstay on most British bartenders’ shortlists. As long as you can get your hands on any berry liqueur, a modified version of The Bramble is easy to make, not to mention thirst-quenching, balanced, and immensely rewarding. Personally, I’d suggest investing in a bottle of crème de mûre and making this your cocktail of the summer – it’s that good.

The Moscow Mule was actually invented by John G. Martin of Heublein, the aforementioned beverage distributor who popularized Smirnoff in the United States. Martin’s friend Jack Morgan, a Hollywood bar owner, had a problem – his girlfriend had inherited a large copper mug factory, and the inventory was at a total standstill. Relatively soon after Martin bought the rights to Smirnoff, vodka had yet to catch on in the cocktail world. The two entrepreneurs developed a gingery cocktail using Smirnoff, served in a copper mug, and ran around Hollywood distributing mugs and Moscow Mule recipes to local bartenders. The drink’s eyecatching look and the exotic, foreign liquor that comprised it immediately took off and became one of the next it-drinks – a neat marketing hack that solved both Martin and Morgan’s business problems.

That’s all for this week. If you enjoyed Issue #2, please give us a follow on Instagram and tell your friends! And as always, if you make any of these recipes I’d love to see photos of your results – feel free to text or DM them to me.

Cheers!

Anna

This was so lit - need issue #3